|

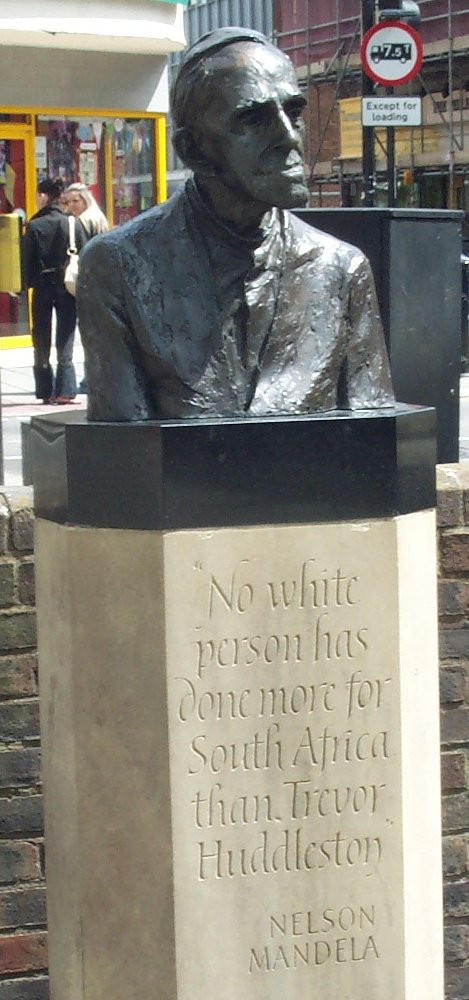

Statue of Archbishop Trevor Huddleston

in Bedford, South Africa (Simon Speed) |

In early 1956 in South Africa, back at school after the summer holidays, an event occurred that changed my life. I was fifteen years old, and selected as one of three girls from my high school class to spend a long-weekend in Johannesburg’s black townships. The Anglican bishop

Trevor Huddleston organized this experience each year, for white school children to meet local leaders and ordinary folk, with the goal of opening eyes to a world normally hidden from their view.

Afterwards, the three chosen from each school would report back, first to the assembled students, then to a parent-teacher’s meeting. I had sat through these presentations before. They were boring. “…And then we got on the bus and went to Soweto. And then we had lunch, and then we got back on the bus….” Nothing life-changing there.

I should explain that while I was growing up, like most whites our family was comfortably cocooned in what I later came to call a ‘cotton-wool society’. My three sisters and I did not know the hardships and injustice inflicted on blacks by South Africa’s

apartheid system. We had a large house, a thirty-foot swimming pool and a tennis court. We had two poodles, and Ruffles the cat. Each August before the rains, we went on a camping safari in our station wagon to a game park, near or far. In summer, my sisters and I and our friends (all white) spent every free moment in and around the pool. Before my parents’ divorce there were three ‘native’ servants - Susan, Mary, and Sam the ‘garden boy’. Last names unknown. Children and other family members unknown. After my father left and money was tight, there was only Susan. The servants’ quarters were at the back of the kitchen courtyard: two small rooms separated by a toilet stall. We children did not go back there. I snuck back only once or twice for a peek.

My “Trevor Huddleston weekend” tore open the cotton-wool cocoon – and changed my world. Our group of twenty-four girls, from eight white high-schools, was based at a suburban convent on the outskirts of Johannesburg. Over three days, we had a busy schedule. Some memories stand out. The black doctors at

Baragwaneth Hospital did not let us into the wards, but they vividly described crowded conditions, and chronic shortage of basic supplies… In

Soweto, the sprawling black township ten miles removed from Johannesburg, row upon row of two-room brick houses were under construction. Each had an outhouse out back, and only one standing faucet for a whole block. We learned that Soweto’s expansion was for families evicted from

Sophiatown, a mixed-race suburb,

which had been bulldozed just months before our visit. Only the Anglican cathedral had been spared. It loomed large and imposing above the rubble. Sunday morning we attended the service there, and I remember tears streaming down my face as I hummed the soaring melody of

“Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (God Save Africa), sung at full voice by choir and congregation.

For me, and I’m sure for most of the girls, those few days were the first time we had talked with ‘Africans’ (as we were asked to call them), who were not servants in our households. And the first conversations we’d ever had about the rules of apartheid that governed our lives. Back at school, I insisted to my friends that we refer to ‘natives’ as Africans. I kept up a refrain – “This system of apartheid is not fair to Africans. It’s WRONG!” My best friend Sally, said “Oh, Judy, let them be – they’re happy just as they are.” Later, the headmistress took me aside and said “Try to be a little pool of quietness.”

When I took my turn at the parent-teacher presentation, again I insisted, “Apartheid HAS to go!” Afterwards, one of the parents came up to me. “You’re fired up now," he said. "Next year, you will go off to college in America.” (I must have mentioned my mother’s plans for me.) “Study well. Come back in four years, then you can work to help get rid of apartheid.” I remember my outrage. Four YEARS. FOUR Years! We can’t wait four years! It must change NOW!

Looking back, I realize I had no idea about how to change the world. I thought that by speaking out loudly and telling people about injustice, they would respond – and change would happen. Bishop Trevor Huddleston was removed from South Africa by the Anglican Church the following year, but he kept up his crusade against apartheid until it ended, thirty-eight years later. After college I did not return to South Africa to participate in “the Struggle.” But to this day I value the weekend experience that changed my world-view.

.jpg)